Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: An Artist’s Inspiration

by Kathleen Lack and Georgia Modi

Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Courtyard of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

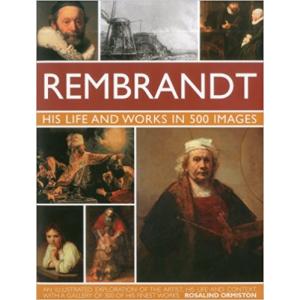

I recently visited the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, which is a stone’s throw from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Built with the intent of creating a cultural epicenter and as the perfect location for an ever-growing art collection. In 1891, Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924) inherited nearly two million dollars upon her father’s death. Initially, she used the funds to grow her art collection, but after purchasing a self-portrait by Rembrandt (1606-1669) in 1896, Isabella and her husband John “Jack” Gardner Jr. (1837-1898) decided they needed more space for their collection. They began considering the idea of a museum, but it wasn't until after Jack's death in 1898 that Isabella went forward and purchased the land early in 1899.

Isabella Stewart Gardner and Others, Snapshots of the Museum During Construction, 1900-1901

Visitors to the museum today will notice that attention was paid to every detail. Isabella prided herself on her daily presence on the job site during construction. Photographs show her standing on a ladder in the courtyard, demonstrating to the plasterers the effect she wanted to achieve for the distinctive mottled pink stucco walls. But it was not only her eye for detail that made this museum something to marvel at, it was also her impeccable ability to create an otherworldly experience. Today, the museum is a visual delight, you truly feel that you have been invited into someone’s Venetian palace for a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Rembrandt van Rijn, “Self-Portrait – Age 23,” (1629), oil on oak panel

Two years into construction and with the museum mostly completed, it was time for Isabella to focus on the collection. It was during this period that she moved into the private fourth-floor apartment and devoted all of her time to personally arranging the art in the galleries. In 1902, Isabella installed her collection of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, furniture, manuscripts, rare books, and decorative arts. She continued to acquire works and change the installations for the rest of her life.

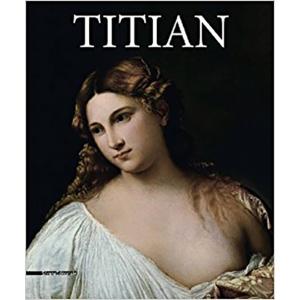

“… downstairs, I feel, are all those glories I could go and look at, if I wanted to! Think of that. I can see that Europa, that Rembrandt, that Bonifazio, that Velazquez et al. — any time I want to. That’s richness for you.”

– Isabella Stewart Garner in a letter to Bernard Bernson, 1898

Titian, “Europa,” (ca.1560-1562), oil on canvas

Isabella built the museum and her collection with a mere two-million dollars, which is a small sum when you think of the eighty-million dollars J. Paul Getty (1892-1976) spent on his collection. So, she had to be smart about what she purchased. With the help of the art historian Bernard Berenson (1865-1959) Isabella was able to purchase Rape of Europa by Titian (1490-1574) from John Stuart Bligh (1827-1896), the Sixth Earl of Darnley in 1896, and it became the crown jewel of her museum.

Spanish Cloister wing of the museum

There is one particular painting that really spoke to me when I visited. Seeing El Jaleo (1882) by John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) for the first time took my breath away. This piece sits within the Spanish Cloister wing, which is your first encounter when you enter the museum. It truly sets the stage for your stroll through the Gardner Museum that will evidently not be a typical museum experience. Rather, a veritable feast for the senses.

John Singer Sargent, “El Jaleo,” (1882), oil on canvas

El Jaleo is a piece that pulls you in effortlessly with it’s almost unconventional sense of drama and eroticism. It was believed that these nomadic Romani were ones to ignore the conventional doctrine of religion, they trudged through countless encounters of oppression throughout the nineteenth century. However, Sargent and other artists revered them as free spirits. It was Sargent’s admiration of the Romani that inspired this work in which he wanted to encapsulate them, to showcase their culture, music, and dance through his marvelous brush strokes! When he began the painting, he chose a wide, horizontal canvas that would lend itself well to the eccentric placement of bodies that give the viewer a true sense of movement throughout the piece. Its shallow proportions imitate that of the typical stage space that many of these Romani would find themselves in.

Original Fine Art For Sale

Kathleen Lack, “Sevilla,” (2019), oil on canvas

Sargent had a true passion for expressing live dance, which is so evident in his pencil sketches of a Spanish woman. He included these in an album that was assembled for Isabella. These sketches have a pace to them, you can feel with quickness of movement with each pass of the pencil. Since my passion for painting lies with the figure, seeing this important work and these drawings by Sargent most definitely made a huge impact on me. Sometime afterwards I was able to go on a trip to Europe and got to experience a performance by flamenco dancers. Well of course I had to paint the scene! I have titled my painting Sevilla. This is a museum of inspiration, it feeds your soul, as any good museum should do!