The Art of French and British Romanticism

By Judith Brown, Serena Kovalosky and Cathy Locke

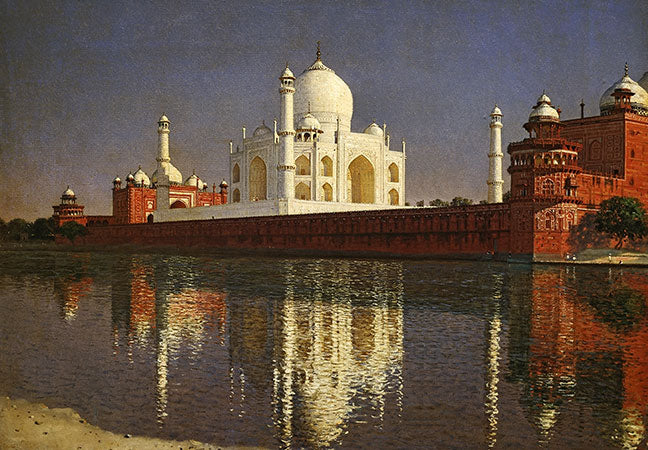

“The Execution of Lady Jane Grey,” by Paul Delaroche, 1833, Collection of the National Gallery in London

Romanticism was a European art movement that also influenced literature and music. The term itself originated in Germany, becoming the banner of profound intellectual and aesthetic changes which we now associate with modernity. It grew out of the Age of Enlightenment during the late 1700s, a period when the educated elite sought to reform European governments. Such thought gave birth to unrest, beginning with the French Revolution of 1789 and ending in 1815 with the Napoléonic Wars. Artistically, romantic painters were reacting to the heavy hand of French academic painting that created the cold severity of the neoclassical movement. In contrast romanticism stressed intense colors, shimmering light, animated brushstrokes and passionate scenes that evoked emotion. One mustn’t be fooled by the softness of the movement’s name, for it represents intense raw emotional expression. Romantic artists fostered a desire to convey their deepest beliefs. If this meant evoking a jarring response, all the better, as they aimed to tap into human emotions rather than intellect. As a result, romanticism became a powerful movement that revolutionized painting forever.

The pinnacle of the artistic movement of romanticism took place during the first half of the 1800s, when artists harnessed the collective spirit of rebellion amongst the common people. This paved the way towards authentic depictions spanning the entire gamut of human feelings, which provoked a move away from the conventional subject matter and techniques that had been employed by the neoclassical artists. The painting The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) by French painter Paul Delaroche (1797-1856), has become an iconic symbol of the romantic tradition. Trained as a neoclassical artist Delaroche used the tragic execution of a teenager, Lady Jane Grey (1536-1554), to abet our emotional response. Upon the death of her uncle King Edward VI (1537-1553) on July 10, 1553, Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed Queen of England instead of his sister Margaret Tudor (1489-1541), the more popular heir. Within nine days of Jane’s assumption of the throne she was forced to step down. She underwent trial for treason, resulting in her execution. Delaroche uses theatrical techniques employed by baroque painters to create a heightened emotional scene moments before her death, a dramatic end to a tragic historical story.

“Liberty Leading the People,” by Eugène Delacroix, 1830, Collection of the Louvre in Paris

The emergence of the romantic movement in France was furthered by the work of painters such as Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and Théodore Géricault (1791-1824). Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Delacroix, captures the rebellious energy of the French Revolution, the symbol of “Liberty” steering the people to their goal of overthrowing the monarch. They are fighting to achieve their ideals, risking their lives. Seen from another perspective, the “power of the people” is threatening the established order, as the painting depicts men of varying ages in different styles of dress, to highlight the coming together of citizens of all social classes. At the same time, it is impossible to overlook the human suffering in this painting. As much as there is a triumphant spirit, there is also a loss of life. This paradox between hope and tragedy gives the painting striking emotional power. Stylistically, there is an absence of convention as diagonal lines and shapes cross each other and smoke blurs the scene through the delicate blending of color.

“The Raft of The Medusa,” by Théodore Géricault, 1818-19, Collection of the Louvre in Paris

Géricault’s The Raft of The Medusa (1818-19) tells the story of a grisly and horrific shipwreck that took place a few years prior to the painting. During this calamity, around 150 soldiers, en route to reclaim Senegal, were left at sea on a raft put together by the ship’s carpenter while the remaining individuals of higher status boarded lifeboats. Géricault does not sidestep the utter bleakness of human suffering that resulted from this abandonment; starvation and death encapsulate the emaciated bodies which the painter has placed right at the center of the painting, forcing the viewer to confront the multitude of emotions on display. A wave threatens to overturn the raft, highlighting the power of nature and the helplessness of these people for whom any hope is likely to be cruelly dashed.

“Titania, Oberon and Puck,” by William Blake, 1786, Collection of the Tate in London

The power of these French artists to devise compelling compositions of complexity and emotional power is why they dominated the romantic movement. British artists interpreted this movement quite differently. Perhaps the absence of any significant combat on the British mainland allowed their artists to take a more impassive approach. British artist William Blake (1757-1827) used the power of his imagination to create fantasy in his artwork. Perhaps the only artist who contributed equally to the romantic literary movement, Blake had a complex relationship with Enlightenment philosophy. His championing of the imagination as the most important element of human existence ran contrary to Enlightenment ideals of rationalism and empiricism.1 Trained at the British Royal Academy, Blake rebelled against the academic painting style that was championed by the school’s first president, Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792). Around 1808 Blake and fellow students created their own artistic group, the Shoreham Ancients, because they had grown to detest Reynolds’ approach to art. This group shared Blake’s rejection of modern trends in art and embraced his belief in a spiritual and artistic New Age. They represented an oppositional break-away from the academic art establishment and looked back to an idealized version of the past.

One of Blake’s earliest and most enchanting paintings is Titania, Oberon and Puck (1786). The painting depicts a scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1605) by William Shakespeare (1564-1616). Its mystical focus, dreamy colors and whimsical nature illustrates Blake’s artistic style, which is technically miles away from the work of French artists of the romantic movement. For Blake imagination was key to the creation of art, he believed that “imagination is not a state: it is human existence itself.” Blake’s entire body of work uses complex and often elusive symbolism and allegory to address issues that concerned him. Blake is considered a forerunner of the nineteenth-century “free love” movement, a broad reform tradition starting in the 1820s that held that marriage was slavery and advocated the removal of all state restrictions on sexual activity such as homosexuality, prostitution and adultery. In Titania, Oberon and Puck Blake illustrates the concept of free love, with his female figures dancing in a circle symbolizing eternal femininity. Nearly 100 years after this was painted, symbolist painters would pick up the baton left by Blake. Though largely unknown during his lifetime, over the years Blake became recognized as a visionary figure.

“Wivenhoe Park,” by John Constable, 1816, Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

To further separate themselves from the neoclassical style, the romantics engineered an idealized restructuring of landscape painting. As the French romantics were enthused by the French Revolution, British artists of the period focused on their local identity. Man’s relationship with nature became a paramount symbolic feature of British romanticism. John Constable (1776-1837) was an English landscape painter, known for his paintings of the area surrounding his home, known today as “Constable Country.” He wrote to his friend John Fisher in 1821, “I should paint my own places best, painting is but another word for feeling.”2 One of his most famous paintings, Wivenhoe Park (1816), is a painting of an idealized view of nature that became known as the English garden. Although his paintings are now among the most popular and valuable in British art, Constable was never financially successful. He did not become a member of the establishment until he was elected to the Royal Academy at the age of 52. His work was embraced in France, where he sold more works than in his native England and went onto inspire the Barbizon School. British Romanticism did not seek to embellish nature, but to elevate it to a more important sphere in people’s lives. Unlike Blake, who painted from his visions, Constable presented nature in its true state, bridging a powerful connection between earth and man.

“The Slave Ship,” by J. M. W. Turner, 1840, Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Considered one of the greatest British artists of all time, Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), known as J. M. W. Turner, was a master at portraying the power of the sea to the point of elevating one’s own consciousness. Like his counterpart Constable, Turner implicitly hints that nature has variable states of being; it is an all-encompassing entity of its own. Romantic artists emphasized nature’s supremacy due to its changeable behavior, thereby underscoring man’s vulnerability. His use of color and lighting was stylistically ahead of his time and had a similar sense of fluidity as that seen in Blake’s work. First exhibited in 1840, Turner’s The Slave Ship (1840), is a classic example of romantic maritime painting. Here Turner depicts a ship sailing through a tumultuous sea of churning water and leaving scattered human forms floating in its wake. His skill as a watercolorist is seen in his fluid blending of color that contributes to the level of turmoil on canvas. The intense, evocative feeling permeating the painting is eponymous with the unique approach of romantic visual art to generate an emotional response.

Summary

Though the romantic movement did not last long in its pure form, the techniques and principles of romanticism soon disseminated into other emerging fields of painting. “The loose brushstroke and powerful palette so characteristic of romanticism has been cited as a major influence on the early impressionist, who capitalized on similar technical elements in their work.”3 The symbolist movement, developed during the second half of the 1800s, can be seen as a revival of mystical tendencies in the romantic tradition, directly developed from the work of artists like William Blake. There is no doubt that the emotional brushwork and abstracting of form by Turner paved the way for sound painting and then pure abstraction. Romanticism renewed “feeling” in painting, placing an emphasis on emotion and originality. These artists created a completely new expressivity in painting that enlivened art for centuries.

Sources

1. Galvin, Rachel (2004). “William Blake: Visions and Verses”. Humanities. Vol. 25 no. 3. National Endowment for the Humanities.

2. Parkinson, “Constable, John,” Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, ©1998, p. 9.

3. William Rau, Nineteenth-Century European Painting from Barbizon to Belle Époque, Antique Collectors’ Club, ©˙2012, pages 41-66.

About the Authors

Judith Brown is a freelance writer who, after obtaining a masters in English from Kings College London, continued to pursue an interest in art. In her articles she draws links between art and literature, showing how both mediums have meaning in today's world.

Contact Information: judithlbrown@hotmail.co.uk

Serena Kovalosky is a sculptor, cultural project developer and film producer who creates and produces projects at the intersection of art, culture and travel. She is the founder of Artful Vagabond Productions whose mission is to celebrate the creativity and inspiration that artists bring to this world and to promote the value of art in an “artful” lifestyle.

Artful Vagabond Productions – www.artfulvagabond.com

Serena Kovalosky artwork – musings-on-art.org/painter/serena-kovalosky

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She organizes annual art excursions to Russia every summer and is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Russian Art Tours – www.russianarttour.com

Cathy Locke’s artwork – musings-on-art.org/painter/cathy-locke