The Two Schools of Russian Impressionism

by Cathy Locke

Unknown Artists of Russian Impressionism

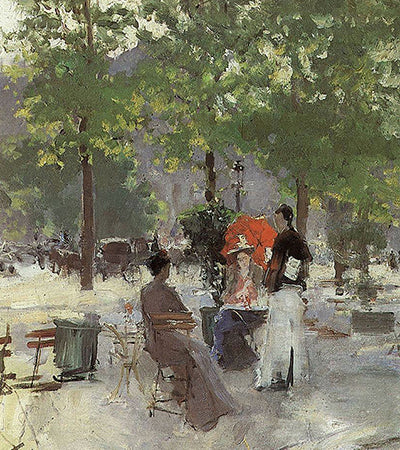

When we think of the artists of the Russian Impressionist movement we think of super stars like Valentin Serov and Konstantin Korovin. However, there are a number of artists who contributed to the movement who have received far less recognition in the Western world. Two such artists are Igor Grabar and Abram Arkhipov. These artists came from different backgrounds and had completely different career paths. Igor Grabar was born in Budapest, where his father was a lawyer who worked in the Hungarian Parliament. Abram Arkhipov came from considerably more humble beginnings, as he was born and raised in a rural village in Russia. Grabar followed in his father’s footsteps and received a law degree. Preferring a more creative path, he enrolled in Ilya Repin’s newly “reformed” Imperial Academy in 1894. He became dissatisfied with the Academy and left for Munich where he studied with Anton Azbe until 1899. His fellow students included Wassily Kandinsky. Arkhipov’s parents painstakingly gathered the funds to send him to study at the Moscow School of Painting when he was only fourteen. His fellow students included Andrei Ryabushkin and Mikhail Nesterov. His teachers included an array of masters such as Vasily Perov, Vladimir Makovsky, Vasily Polenov and Alexi Savrasov. After graduation, at the age of twenty-six, Arkhipov spent the rest of his life as a teacher.

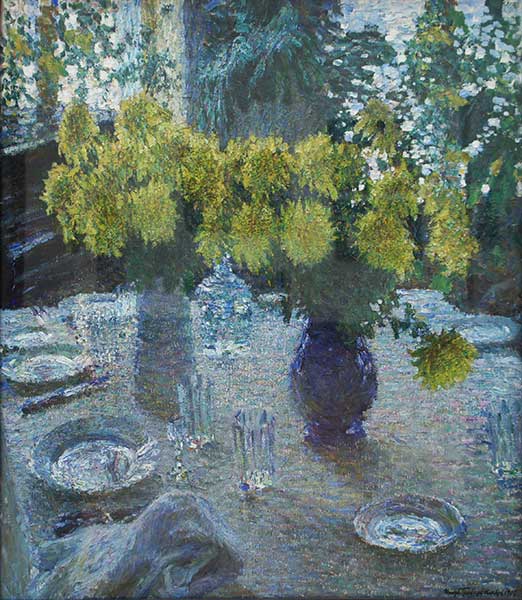

In their own unique ways, both Grabar and Arkhipov, contributed greatly to the advancement of Russian Impressionism. In 1905 Grabar traveled to Paris where he studied with the Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists. He developed a painting technique that was closer in style to the Post-Impressionists than any of the other Russian painters. He practiced a form of Divisionism and incorporated Pointillist techniques where brushstrokes are laid next to each other but do not mix. Because of this technique Grabar's paintings do not contain any hard edges; they are soft snapshots of beautiful light falling over still lifes of the aristocratic elite. There is an enormous amount of sensitivity to color within Grabar's paintings. Though his palette is primarily cool, the range of color he is able to achieve is remarkable. His work is a wonderful refined blend of academic training combined with techniques developed by the European Impressionists.

By 1891 Arkhipov was an active member of the Wanderers, a group of Russian representational artists who painted themes dealing with the inequities and injustices of life under Tsarist rule. During this time he painted plein air landscapes along the Volga River using muted colors to create a moody effect. In 1899 Arkhipov created one of his most famous paintings, The Laundresses (also titled The Washer-Women). The painting captures the spirit of oppression that was felt by most of the factory workers during this time. The colors are muted, as the scene epitomizes the hopelessness of these women’s existence.

Around 1910 Arkhipov started painting a series of portraits of peasant women from his hometown region. In these paintings the figures are dressed in bright national costumes and painted with broad decisive strokes. From here forward the theme of peasant life would dominate his work for the rest of his life. His painting style began to change from his earlier detailed work to a more expressive and passionate style. As a fellow teacher I can almost picture Arkhipov's life by reading his paintings. I can see him rushing from the classroom to his studio, making the most with his time, he had already thought out each brushstroke before arriving to his studio. When you look at his work you can feel his confidence with each stroke. Arkhipov painted with thick paint letting colors from underneath come through. He used a strong value pattern to lead the viewer's eye around the picture plane. Unlike Grabar Arkhipov's technique is not soft and sensitive, but bold and assertive. Also, unlike Grabar's cold aloof work, Arkhipov's work is filled with the heart and soul of the Russian people. The Moscow branch of Russian Impressionism became known for its warm ochre colors, which I am sure came from Arkhipov's delicious warm palette.

Arkhipov died before Stalin’s 1932 decree that marked the beginning of Soviet Realism, a style forced upon Russian artists where they had to work with themes based on “happy Soviet life.” One has to wonder if Soviet propaganda had any influence on Arkhipov’s work, especially since he taught in Moscow near the government Duma. During the last ten years of his life Arkhipov’s peasant paintings conveyed happy Russian people. The days of his gray muted paintings like The Laundresseswere gone forever.

I don’t know if Grabar and Arkhipov actually knew each other. They came from two completely different walks of life and I imagine their personalities were totally different. Grabar was an intellectual who supplemented his income by writing for the World of Art’s magazine Mir iskusstva, as well as a number of other publications. His relationship with other artists was strained due to his well documented superiority complex. In 1908 Grabar abandoned painting and began writing a number of books and articles on the history of Russian Art. In 1913 he became the executive director of the Tretyakov Gallery. It was due to Grabar’s efforts that the museum expanded its collection to include contemporary art as well as icons. After the Revolution of 1917, Grabar incorporated large quantities of “nationalized” artwork into the collection. The artist received a number of high-ranking positions within the Soviet regime and many of his old "friends" felt he was doing nothing more than stealing artwork, earning him the nickname “cheating eel.”

After his mother’s death in 1930, Grabar left all of his administrative and editorial jobs to concentrate on painting. Grabar painted a string of official pieces in the Soviet Realist’s style including a portrait of Stalin’s daughter at a much older age than she really was at the time. Grabar’s attempt at publicity backfired and he was forced to retire his paintbrushes.

Little is known about Arkhipov’s personal life here in the West. Besides teaching at the Moscow School of Art (1894-1918), he also taught at the State Free Art Studios (1918–20) and then at VKhUTEMAS in Moscow (1922–24). In 1903 he became a member of the Union of Russian Artists. After World War I in 1924 he joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR). In 1927 he was awarded the title of People’s Artist of the Russian Republic.

About the Author

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com