Masters of Portrait Painting: From John Singer Sargent to Ilya Repin

by Cathy Locke

I have tried to keep my obsession for portraiture in the closet for a long time, but at long last I am going to expose myself. I started studying portraiture seriously in the early 1990s when I was lucky enough to find one of San Francisco’s gems – Bob Gerbracht (1924-2017). Bob, well into his eighties, still continued to teach three classes a week to an eager group of adult students. He certainly puts the “P” in “pickiness” and I remember many portraits that I did in his class where he had me laboring over moving a “perfectly” painted eye or nose one-eighth of an inch to the right or left. He instilled in me the importance of measuring accurately to achieve a likeness. When it came to color, Bob taught me to paint what I saw by observing the subtle color changes in the face. I learned that the forehead tends to be more yellow, the cheeks more red and the chin more green. Watching Bob paint was the first time I ever noticed how oil paint could look like butter when properly applied. He knows how to lay the paint on the portrait with just the right color and the right stroke, going in just the right direction. Those types of observations are what I look for in a good portrait. I still use Bob’s system of measuring and process for color application today and in fact I teach his method to my students.

This diagram demonstrates Bob Gerbracht’s measuring system. He takes the shortest measurement of the head, usually the width, and puts it into the height to see where it lands. I like using a square to show this concept to my students because a square is as high as it is wide. I create a square the full width of the head and I place it under the chin. I use the chin because it is usually a clear landmark on the face. Once the square is created I divide it in half and then again into quarters. I recreate this square on my canvas. This allows me to tell where the features are located on the face and their size.

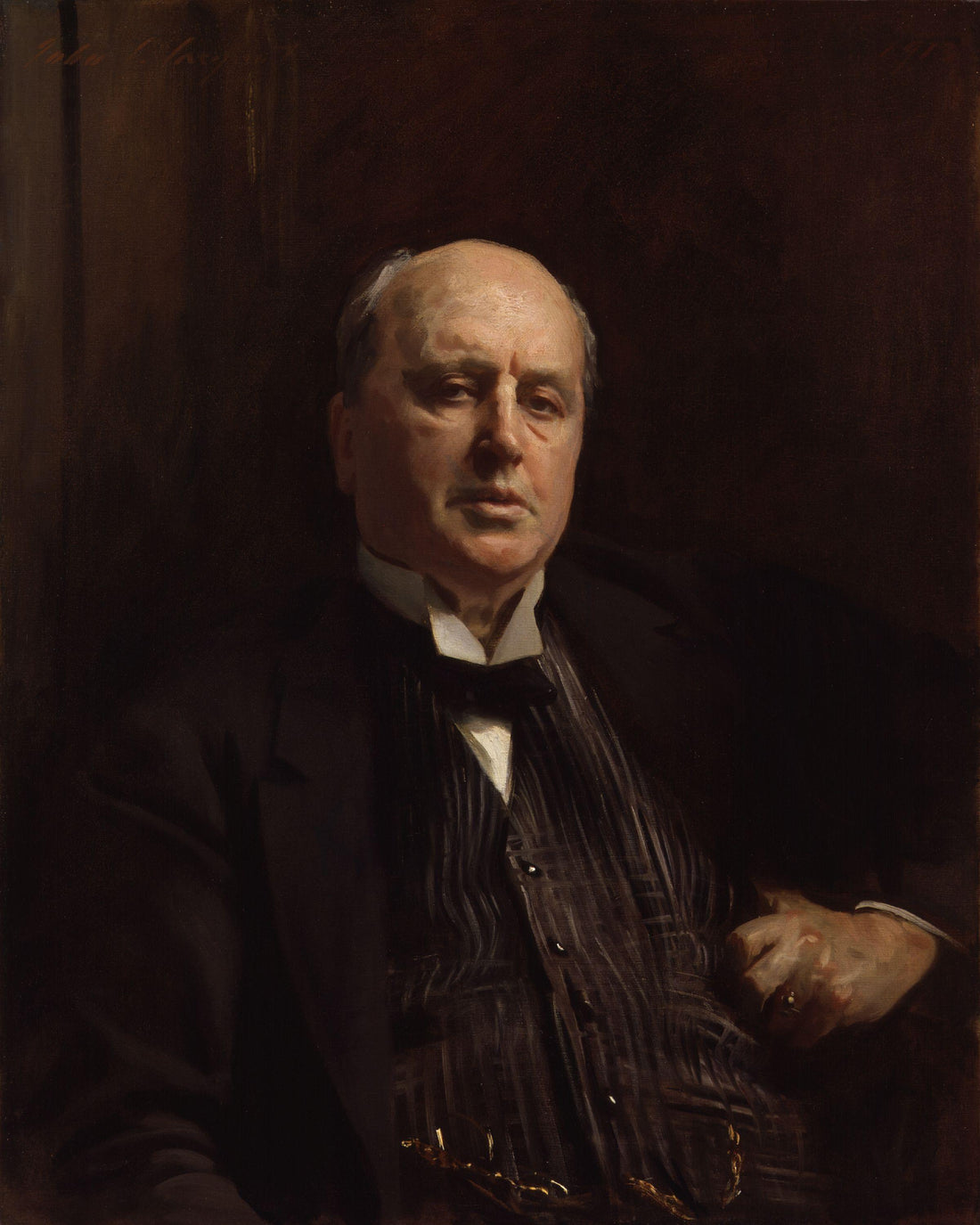

Bob had an old stool in his studio that he claimed was once owned by the “father of American portraiture,” John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). According to Bob, if you sit on this stool and moved your fanny around, some of Sargent’s magic would rub off on you. Since I never felt the “magic” was rubbing off fast enough, I decided to go see a retrospective of Sargent’s work in Boston during the fall of 1999. I remember standing in the main room of the retrospective and being absolutely amazed at these huge, highly accomplished portraits. His paint application has a wonderful, silky-smooth quality accomplished with a good amount of medium, probably linseed oil. Though his work is highly blended, the last strokes of paint that he applied seemed to sit on top of the painting, helping reinforce the shape of the form underneath. It is my understanding that Sargent used a fairly limited palette for his skin tones, which consisted of: lead white, vermilion, bone black, rose madder and meridian green. It’s an interesting combination of colors, primarily a cool palette with the exception of the vermilion. It does show his variation in color for skin tones: from the green we often see around the lower third of the face to the variation in cool to warm reds in the cheeks and nose area.

John Singer Sargent was the first master portrait artist of international acclaim with whom I became completely obsessed. When I heard Sargent’s famous quote: “A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth,” I knew I was in love with him! I believe I have seen every retrospective of his work within the United States over the last twenty years. As well, I believe I own every book ever published about him: books on his portraits, watercolors, “Sargent and Italy” and Deborah Davis’ lovely book “Strapless.” Even though he is referred to as the father of American portraiture, he was actually born in Florence, Italy (1856), raised throughout Europe, studied in Paris and spent most of his later years in England. At eleven Sargent was fluent in French, Italian and English. The only “American” thing about him was his parents, but nonetheless we have claimed him as our own. Sargent’s childhood consisted of painting with his mother in their home studio in the mornings then painting outdoors in the afternoons, with frequent trips to museums to study such masters as Tintoretto, Michelangelo and Titian. He had a childhood that would make any artist envious.

In 1874 Sargent began his formal studies with Charles Auguste Émile Carolus-Duran (1837-1917), one of the most successful portrait artists in Paris of his time. Upon first reviewing Sargent’s portfolio for admission into his atelier, Carolus-Duran proclaimed that Sargent’s work gave evidence of “much to un-learn,” but he showed “promise above the ordinary.”1 Carolus-Duran came to Sargent's atelier on Tuesdays and Fridays to review the student’s work. He did not charge his students a fee, as was the custom, but instead made his living from his own work. Duran would give each student a detailed critique, often writing directly onto their work. His system for teaching portraiture was as follows:

The student began with a sketch made directly onto the canvas, checking proportions through sight-measuring with a stick of charcoal. The main planes of the face were massed in with a broad brush so that the face looked like a mosaic. No smoothing of the edges between the planes of the face and features were permitted. In this method the student was taught to first build a solid architecture for the face. In the “architecture” phase, color was not a concern to Carolus-Duran, only value comparisons. Color was applied on top of the edges between the planes of the face and blended into each plane.

At the age of twenty-one (1877) Sargent’s portrait of his friend Fanny Watts was his first painting to be accepted into the Paris Salon. In those days the Salon was an extremely important vehicle for artists to advertise their skills to find patrons. During the next ten years Sargent’s fame skyrocketed and his work won awards each year at the Salon. Early in 1883 he began what is probably his most famous portrait, that of Madame Gautreau (1859–1915), known simply as “Madame X.” Gautreau and Sargent shared a desire to climb the Parisian social ladder and both parties wanted to create a portrait that would gain attention at the Paris Salon. Sargent spent over a year agonizing over this portrait. The final painting was a highly stylized, life-size full figure portrait. Gautreau was painted in a low-cut black evening gown with her head turned to the side and one strap falling off her shoulder. Her skin was a pasty white color from the powder the women of that period applied to their skin. When the portrait was first displayed on May 1, 1884, it set off a small riot at the opening. The public considered it scandalous because of the fallen strap. They felt it looked like she had just had sex or was about to have it. Since she was looking away from the viewer in the painting, it made her appear indifferent to social protocols. Unfortunately for both Gautreau and Sargent, the portrait had disastrous outcomes for their lives. Gautreau’s husband ostracized her and sent her to live in the countryside with her mother and Sargent left Paris to settle in England. Though his dreams of success in Paris were over, Sargent went on to have a very healthy career in both London and Boston. Sargent later painted over the shoulder strap, securing it to the top of Gautreau’s shoulder. In 1916 he sold the painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and always felt it was his best work.

Learning from Russian Portrait Painters

My first introduction to Russian painting was through the portraits of Valentin Serov (1865–1911). During my first trip to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow I had to be physically peeled off the bench in the room that displayed Serov’s portraiture work. I was not only fascinated with his color palette, which at the time was new to me, but also with the artist's ability to capture a unique feeling about the person he was painting. It wasn’t until many years later that I learned of Serov’s psychological approach to portraiture. It was through his teacher, Ilya Repin (1844–1930), that Serov learned to take a psychological approach to his work. Serov’s portraits read like a good Russian novel, always making a statement about the person he painted.

In his portrait of Sofia Botkina we see a beautiful woman sitting on a sofa with her little dog. If you look around this painting, that is all you see - the room is empty and Serov has used very muted grayed tones. He is saying she wasn’t the most exciting person and there isn’t much to her. In total contrast, his portrait of Princess Zinaida Yusupova is filled with activity and opulence. The way Serov posed the princess plays up her sexual attractiveness, which was thought to reflect her vacuous life. The critics called this painting “a bored bird in a gilded cage.” Another thing that I love about Serov is that, like myself, he was a slow painter. It took him three years to complete the portrait of Princess Zinaida Yusupova: a total of eighty sittings of two hours each. It is said that he so enjoyed her lifestyle and personality that he wanted to extend the experience. The family joked that the dress she wore grew increasingly tight.

About the time Serov first started to acquire some notoriety (1885), his style was considered very new; it was highly influenced by the Impressionists and what was coming out of France at the time. Serov used a technique called color blocking. He would begin a portrait by creating the overall shape of the figure first and then, with one color, he filled in that shape. He moved around the canvas creating the overall shape of each object and filling it in with one color. This technique was very similar to what Gauguin was doing at the time called Synthetism. Gauguin’s Post-Impressionistic style flattened form creating two-dimensional flat patterns. Serov was always searching for the right colors to show the true personality of the person he was painting. Though Serov’s brushwork is influenced by the French Impressionist painters he never completely embraced their use of color. Instead we see more gray or silvery tones in his work, influenced by Anders Zorn (1860-1920), a Swedish painter. The “Zornish” manner first appeared in Russian painting when Serov and his friend Konstantin Korovin took a trip together to northern Russia to paint. By the mid-1890s the technique had become very popular with the Russian painters, especially those living in St. Petersburg. The Moscow painters tended toward golden ochers and rich reds. With Serov’s work you will see a use of both Zorn’s gray umbers and the Muscovite painters' golden ochers. In many of his portraits we see what I call Russian green, which is a mixture of raw umber, yellow ocher and cerulean blue.

The 20th century Russian painter Sergei Bongart (1918–1985) described Ilya Repin as “the fountain head of all modern Russian painting,” from whom a great wealth of painterly knowledge and painting technique flowed and flooded the land. 2 Ilya Repin is probably the most famous of all the Russian masters. He painted portraits of people from all walks of life - from nobility to peasants. Repin himself came from very poor beginnings and as he rose to the heights of success, it gave him the ability to be equally sympathetic to all people. Though he lived during a time of tremendous experimentation in the art world, his style remained closer to that of the old European masters, especially Rembrandt. A lot of people mistakenly refer to Repin as a Russian Impressionist, but he wanted to be referred to as the Rembrandt of Russia.

Several of Repin’s teachers had a strong effect on his style of painting. He learned to draw and paint the human form from Ivan Kramskoi (1837-1887), however the two used color very differently. Kramskoi employed little color in his portraits whereas Repin’s work is rich with saturated color. Both artists used very simple compositions. Kramskoi built up detailed textures in the hair, skin and clothing of his sitters in a manner similar to that of the Venetian master Titian (1488-1576). Though equally as well-rendered as Kramskoi’s work, color became the dominant feature in Repin’s work. Pavel Chistiakov (1849–1861) taught Repin how to take a psychological approach to his work. Even in his simple portraits, Repin poses his sitters in such a way as to tell a story about them. Repin was a very fast painter; he was able to finish a formal portrait in a matter of days. He often had students who would work for him to finish minor details.

Putting it all Together

There are certainly many ways to approach portraiture and, as artists, we soak up what we see in other artists' work. In the paintings of Sargent, Carolus-Duran, Kramskoi and Repin, we see a more traditional approach where the subject is pretty much front-and-center with very little else going on. Both Gerbracht and Serov have added a narrative that tells a story about the individual being painted. I have approached portraiture both ways. In one of my latest series of paintings, which are a series of portraits of children, I have tried to describe their personalities. In my painting, “Puppet Show,” instead of doing a straightforward portrait, I wanted to paint something that shows the creative personality of its little puppeteer. I have to confess that you can probably see a heavy influence of Serov’s color palette in all of my work. As artists it is important for us to go to museums, see the actual paintings and study them. And then to take what we learn and continue the journey of learning by pushing ourselves with each new painting.

About the Author

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com