Surrealist Artists and Their Poets:

Rousseau-Apollinaire and Kahlo-Breton

By Judith Brown

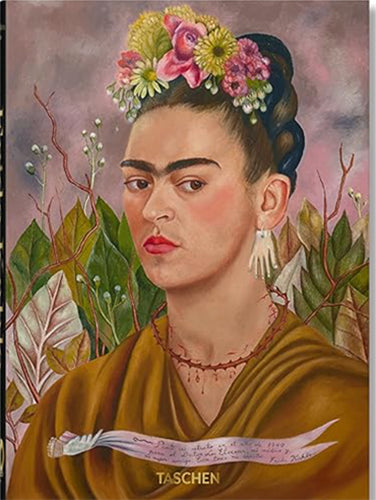

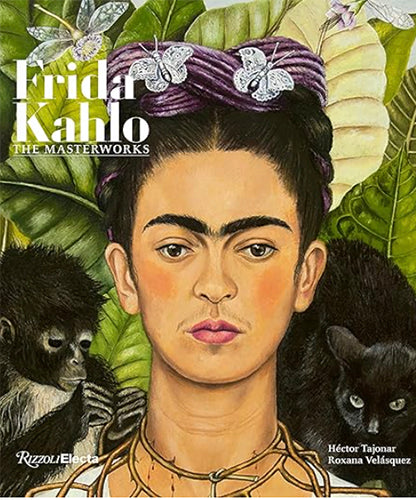

Neither Henri Rousseau nor Frida Kahlo described themselves as surrealists. In the case of Rousseau, the term had not yet even been coined during his lifetime. As for Kahlo, she objected to her work being described as such. Indeed, in some volumes on surrealist art we find no mention of either artist (1). Yet both artists had relationships with poets who played pivotal roles in the surrealist movement as we shall see.

In the big picture both artists fit into the broad sweep of surrealism – the “automatism”, the freedom from convention, the revelations of what Freud describes as the “id”, all included – though exceptionally positioned: Rousseau at the dawn and Kahlo in the twilight. Those “times of day” for surrealism in art were of course unrecognized by contemporaries including the poets. For example, Andre Breton, the surrealist poet who promoted Kahlo, had no intimation in 1938 on his trip to Mexico that within a few years all would be over for this movement which he had played such a large part in promoting. Guillaume Apollinaire, Rousseau’s poet, as we shall see, had more of an intuition about his participating in the dawn of surrealism than Breton had about sharing in its twilight.

Rousseau and Kahlo, in having a strong connection to a poet, conformed to a pattern that was intrinsic to surrealist art. Normally before surrealism the role of artist in poetry was as illustrator. With surrealism, the poet becomes the interpreter of the artist – explaining to viewers what it is all about. Granted, such explanation is less needed for Rousseau at the dawn and Kahlo in the twilight than those artists in the morning, midday, and afternoon, of surrealism.

Before digging further into that issue of poet as surrealist illustrator, let’s remark on an important similarity between Rousseau and Kahlo which transcends in some respect their surrealism albeit in other respects adding to that concept’s wide appeal. This was their “naivete”. Rousseau lacked formal schooling as an artist and his “simplicity” and even “defiance” of convention became a key element in the attractiveness of his work not just to “the public” but also importantly to key contemporary artists. This naivete in turn added to the fertility of the ground in which the seeds of surrealism grew. His poet friend, Apollinaire, understood intuitively that fertility. And so did Breton in his encounter with Kahlo.

Today, with works of both Rousseau and Kahlo fetching eight figure dollar sums at auction, we could say that the art-consuming world has fully recognized all these distinctive points about each artist including the story of their poets. And both artists have gained popularity it seems from their own streaks of realism and hyper-realism which contradicts in some respects the poetry of surrealism. Both artists’ focus at one stage of their lives on still-life creations fits in with this. For Rousseau that focus was early in his life, for Kahlo late; but the pre-occupation with still-life adds a dimension to their work overall which resembles that of say Monet’s waterlilies to the life’s work of that great impressionist.

Rousseau-Apollinaire

Apollinaire and Rousseau formed their special relationship when the painter was already advanced in years yet in his artistic career still widely unrecognized. Apollinaire by contrast was young. That is quite the opposite way round as we shall see for Breton and Kahlo. Apollinaire was deeply struck by and an admirer of Rousseau’s work – impressed by his naivete and thereby his ability to break with convention and become open by remarkable intuition to drive forward “modernist themes” which neither would yet describe as surrealist. Apollinaire played a huge role, as an important art critic with what we would describe today as live networking within his considerable artistic circle, in the promotion of Rousseau’s work. Examples include the introduction to Picasso and the art world at a burlesque banquet held by that artist in 1908 in honour of Rousseau 1908 (2), or the introduction to the American cubist, Max Weber, on his visit to Paris, and the latter’s successful exhibition of Rousseau’s work in New York.

Rousseau paints Apollinaire twice under the title of “The Artist and His Muse” (1908-1909) – a picture of Apollinaire and his romantic partner (and cubist artist) Marie Leurencin.

Rousseau, “The Poet and His Muse” (1908-1909)

Rousseau, “The Poet and His Muse” (1908-1909)

Apollinaire’s partner was in turn the inspirer of his collection of poetry under the heading of “Alcools” published in 1913 (see below). In 1910 shortly before Rousseau exhibited his last great work “The Dream,” he appealed to Apollinaire “You will unfold your literary talent and avenge me for all the insults and abuse I have experienced.” We have some evidence of the poet’s response in his inscription on the gravestone of Rousseau (1912) (3):

“We greet you

Gentle Rousseau, you hear us

Delannay his wife Monsieur Quaveland

Let our luggage pass free through heaven’s gate

We’ll bring you brushes, paints and canvasses

So that you can devote your sacred leisure’s

In the Real Light to painting, as you did my portrait

Painting the Face of the Stars”

We see here Apollinaire’s recognition of Rousseau’s portrait of his poet-friend (the painter and his muse) and also this verse reveals an example in poetry of the modernism both men sought. And we should note that it was Apollinaire who in 1917, just a year before his own death in the Spanish flu pandemic, who “coined” the term surrealism. This was in his program notes describing the ballet Parade, a collaborative work by Jean Cocteau, Guillaume Apollinaire, Erik Satie, Pablo Picasso and Leonide Messine.

In the poetry literature some commentators see Apollinaire’s poem about the Mirabeau Bridge published in the Alcool collection (4) as illustrating best his path towards modernism and indeed surrealism.

“Under the Mirabeau bridge flows the Seine

And our loves

He has to remind me of that

Joy always comes after pain”

The lack of punctuation allows words and images to flow into each other. In parallel, the river Seine flows through the poem. Another sign of the poem’s modernity lies in Apollinaire’s choice of a bridge that had only recently been constructed (at the time of writing). Everything but the bridge and the poem itself is transient. Critics have noted that the clasped hands of the lovers mirror the bridge.

Does the poem sound an existentialist note? Yes – and there lies an important common thread here between the works of Apollinaire and Rousseau. We see amongst the creations of Rousseau so many portraits of ordinary men and women in a world of their own deep in themselves. (see for example “portrait of a red-haired man” below).

Rousseau, “Portrait of a Red Haired Man” (1894)

Connection with Cezanne? Of course. The art history literature speculates about the influence of Cezanne on Rousseau, mostly via the channel of cubism; the link of existential contemplation can only be inferred indirectly. Certainly, “Cardplayers” by Cezanne (1890-1892) have been hailed as an example of existentialism in art – portraying abstract feelings of freedom and choice, dread and doom, identity and self-realization (5); these are all themes which can be traced back in literature to Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground” published a quarter century earlier.

A famous quote from French existentialism (Jean-Paul Sartre) is “I am therefore I think.” This puts on its head the original Descartes formulation of “I think therefore I am”, meant to demonstrate the primacy of man’s rationality. We might say that Rousseau would have immediately recognized the truth in the re-statement by Sartre. Rousseau had an intuition across a broad spectrum of modernism and more broadly new thinking which were to sweep through European art and literature in the two decades after his death (2012). Existentialism was one of these. And related to this, predating in some respects, were the themes of the animal in man, and the subconscious as against rational drivers of human action.

We can think here in literature of Zola’s developing in his “Human Beast” the concept of an uncontrollable jealousy coupled with a maniac drive to kill as personified in the engine driver (Lantier). The idea of the animal in man – and the delving into how man is both animal and more – was germinating in contemporary literature alongside the Freudian concepts of id and ego. The uncomfortable and puzzling relationship between the two is the subject of Kafka’s “A Report to An Academy” by a professor who was originally an ape. We should mention Apollinaire’s own concern with the animal in the human as illustrated in his series of poems “The Bestiary” (6) about animals, surely stimulated in some way by his connection with Rousseau. For example:

“Lion

O Lion, unhappy image,

Sadly fallen kings,

You are now born only in a cage

In Hamburg among the Germans”

Rousseau, “The Sleeping Gypsy” (1897)

For Rousseau the lion comes into his famous work “Sleeping Gypsy” (1897) - a lion musing over a sleeping woman with a mandolin on a moonlit light. Rousseau like Van Gogh had a predilection for night scenes. The emotion and intent in the lion’s eye are indiscernible – perhaps he is protective of the woman? This mixture of the incongruous, the direct expression of the subconscious, the irrational connections are all the stuff of what was later to be described as surrealism. We see this again in Rousseau’s last and great work “The Dream” which in its expression of the subconscious features the portrait of Judwigal (Rousseau’s Polish mistress from his youth) lying naked on a divan gazing over a landscape of lush jungle foliage including lotus flower, animals including birds, monkey, an elephant, a lion and a snake. There is no tiger in the scene, maybe because it would be difficult to include this animal without it becoming central to the picture’s narrative – which it certainly does in an earlier work “The Surprised Tiger in a Tropical Storm”.

Rousseau, “The Dream” (1910)

The tiger is surprising its unseen prey – there is a dream-like quality in the luscious vegetation. Rousseau later claimed the unseen victim of the surprise attack is a party of ambushed explorers.

Rousseau, “Surprised Tiger in a Tropical Storm” (1891)

The incongruous fascinates both Rousseau and Apollinaire and we encounter this in both their work. But as noted we also find hyper-realism – for example Rousseau’s depiction of children as adults and this is often in scenes where the normal proportions of distant and near are totally distorted. Hyperrealism here does not mean a careful photographic representation but depiction of the reality underneath the façade. That is a key distinction which come to the fore in our analysis below of the Kahlo-Breton relationship.

Rousseau, “Child with Doll” (1892)

Kahlo-Breton

The relationship of Frida Kahlo to her poet, Andre Breton, is different in several respects from that of Rousseau to Apollinaire.

For a start, there is complete age reversal (Breton the elder, Kahlo young starting her artist career) and fleeting (Breton’s connection with Kahlo extending two years only, though longer if we include his wife, Jaqueline Lamba). There was none of the mutual personal devotion we found in the case of Rousseau/Apollinaire. Yes, there is the similarity of the poet also as the promotor (of the artist’s work) and the artist seeking out that connection. The poet for Kahlo was searching for an artist who would fit in with his Mexican surrealist image, for Rousseau, at the time of his connection to Apollinaire, no one was yet referring to surrealism.

Breton’s voyage of discovery which resulted in his meeting Frida Kahlo started with his conviction that “Mexico was the embodiment of surrealism” (7). What did Breton mean in that phrase? Perhaps it involved a combination of Mexico’s “exuberant nature,” the myths and mystique of its pre-Columbian history, the ways in which its culture conciliated life and death; all of this could explain Mexico’s privileged place in the surrealist imagination.

This French poet had launched his manifesto of surrealism in 1924. As a one-time medical student who had come under the influence of modern psychoanalysis and nascent psychiatric research, his writing and indeed life’s work derived its strength from this source.

It was in 1915, when Breton had been drafted and served in the neurological ward of a military hospital. It was there that he met a severely wounded Apollinaire, who was a volunteer in the French army at the start of World War I. They became close friends and Apollinaire had later introduced Breton to Philippe Souppault and Louis Aragon, both poets and writers, who together with Breton were to subsequently jointly launch and edit the surrealist review “Literature.”

Breton regarded Freud’s findings as the fortuitous rediscovery of the power of dreams and imagination – an antidote to contemporary smug belief in technical change. In his manifesto Breton had defined surrealism as psychic automatism; the artist and poet expressed the creative force of the unconscious. They worked in a hypnotic or trance-like state, recording the train of mutual associations without censorship or attempts at formal exposition. They believed symbols and images produced though strangely incongruous settings constituted a record of a person’s unconscious psychic forces.

We can say that Breton played a formative role in surrealism, but this never became a cohesive movement despite his best efforts. Indeed, a rival manifesto by other surrealists (led by Yvan Goll) was issued virtually simultaneously with the 1924 launch of Breton’s. In 1929, Breton had published a second manifesto which stressed the benefits of “collective action,” but this was of course anathema to for example the Dadaists (anarchists) who might also fall under the surrealist description. There were recriminations and expulsions from Breton’s inner group. Breton himself had become a member of the French communist party but was expelled from this in 1935 following his public rebuking of Stalin’s mass execution of intellectuals.

In April 1934 Andre Breton had married the artist Jacqueline Lamba, in a joint ceremony with Paul Eluard who married artist Nusch Éluard. Eluard was a close friend and surrealist poet, an enthusiast of automatic writing and collage (incongruous associations). This wedding took place just two months after the failed fascist coup in Paris at the peak of the so-called “Stavisky Affair”.

Some readers may see a parallel between Apollinaire and his muse Marie Laurencin with Breton and Lamba, but the differences are greater than any parallel; and the poet in each case was not illustrator for his muse but deeply inspired by her; the poet as illustrator for surrealist art happened in the world outside that of personal union (Rousseau for Apollinaire and Kahlo for Breton). A parallel was that both muses were artists. As such, Lamba’s focus was on use of light, nature, and from 1934 her work fitted in with surrealism). Her fluency in English facilitated her spreading Breton’s surrealist manifesto and regular follow on to English-speaking audiences, important to the success of this art movement in shows in New York or London. A communist, she remained in the Party even after Breton’s expulsion in 1935.

It was the political activism of both Breton and Lamba that helped to bring them into contact with Frida Kahlo. Frida Kahlo’s husband, Diego Riviera (20 years older than Frida, his third wife, married in 1929), was already a celebrated artist, especially for his murals, and had been inspired by the political ideals of the Mexican revolution (1914) and the Russian Revolution 1917. Nelson Rockefeller had ordered that his famous mural be removed from the wall of the RCA building (the mural had included an impersonation of Lenin) and amidst the controversy this had brought much publicity to Riviera.

In 1936, when Norway was threatening to expel Leon Trotsky, who had been granted temporary asylum there. The Rivieras had influenced the Mexican government to grant Trotsky asylum. They promised Trotsky the use of their villa, “La Casa Azul” (the Blue House) near Mexico City. This house was part of Kahlo’s family and a place where she spent much of her life, today it is a museum. Trotsky lived at La Casa Azul from January 1937 until April of 1939. The living arrangement ended when there was a row between Riviera and Trotsky. Some say over ideology, others say it was because of a brief affair between Frida and Trotsky. He set up residence in another house nearby where he was assassinated in August 1940 by a Spanish agent of Stalin.

Anyhow that is running ahead of our story. Let’s backtrack to the poem which Breton wrote as inspired by his marriage to Lamba, with whom some say he was infatuated, translated into English as

“Freedom of Love” (see 8):

“My wife with the hair of a wood-fire

With the thoughts of heat lightning

With the waist of an hour glass

With the waist of an otter in tail of a tiger

My wife with the lips of a cockade and of a bunch of starts of the lost magnitude

With the teeth of tracks of white mice on the white earth”

We see here Breton’s poetry at the peak of its surrealist vigour – whether in terms of automatism, more generally the unconstrained and unformatted expression and stark imagery of the subconscious; and some would note the connection with the tiger and the role this animal played in the paintings of that artist at the dawn of surrealism, Henri Rousseau.

Early in 1938 Breton and Lamba set off on a planned four-month trip to Mexico. This took place on the commission of the French government, the Front Populaire. This government was a included socialists and communists under Leon Blum, who was in power between Spring 1936 and Spring 1938. The trip came at a critical time for Breton, whose surrealist group was in crisis due to the reactions in the artistic world to the power of fascism in Europe and in particular to the government’s failure in France to supply material to the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War when it erupted in 1936. Whilst calling for solidarity with anti-fascism Breton had insisted on art’s autonomy and on maintaining “automatism” as the principal motif. Other surrealists had deserted his movement in response including prominently Paul Eluard with whom he had been so close.

Breton had hopes that the Mexican scene would help rescue his movement. Mexico presented an alternate possible situation outside the European problems. He was scheduled to give a series of lectures on modern art to the National University of Mexico. But he only gave the first lecture before the series was terminated by political turmoil in Mexico (see 9). But that was not in fact the chief purpose of his visit. Rather top of the list was his meeting with Trotsky, for whom his association with the Rivieras was crucial in realizing.

Sparking the political turmoil was an attempted but failed coup against the Mexican President Cardenas (who incidentally had granted asylum to Trotsky, having been assured by Rivera that he would provide accommodation for him – in fact at the residence belonging to Kahlo). Breton set to work, together with Riviera and Trotsky, on a Manifesto for an independent new art, upholding “aesthetic autonomy” in contradiction of Stalin’s stiffening restrictions on production of art in the Soviet Union. Ultimately, the document was signed by just Riviera and Breton. Following his visit to Mexico Riviera’s writings on his trip met some criticism – either regarding “romanticism,” the effort to fit what he saw into “art primitivism;” and explicit criticism of his continuing failure to engage fully at a political level.

How to fit his encounter with Frida Kahlo into all this? The Bretons staying on arrival in Mexico with Riviera’s first wife, Guadaloupe Marin (an “exotic beauty” who had married Riviera in 1922, both then members of the Mexican communist party), contacted Diego and Frida; from there came the connection to Leon (Trotsky). Andre Breton was not disappointed in his hope to find the surrealist catalysts he had hoped for in Mexico. In seeing Kahlo’s composition “What the Water Gave Me” (1938), which was not yet completed, he excitedly pronounced this to be a work of great surrealist importance. The work exhibited the following year in January 1939 in Paris. Kahlo took it back to Mexico and used it to settle a $400 debt to her photographer.

Kahlo, “What the Water Gave Me” (1938)

Art critics of “What the Water Gave Me” have noted that we see reflections of subconscious images in Kahlo’s mind of life, death, happiness and sadness. In the middle of these images lies Frida herself. She seems drowned by her imagination. Blood is coming from her mouth.

Kahlo said later “they thought I was surrealist, but I was not. I never painted my dreams. I only painted my reality.” (see 10) And it is indeed difficult to think of any painting more “hyper-realist” than her 1932 work depicting her delivery of a dead male foetus (the Henry Ford Hospital). Anyhow her great chance came when Breton arranged to exhibit her work in New York, an event at the Julien-Levy Gallery, which turned out to be a great success. Breton invited Kahlo to come to Paris, which happened in early 1939. She did not enjoy the visit, was apparently underwhelmed by promised sponsorship from Breton, though there was an exhibition (March 1929) of her works at a private gallery specializing in surrealist art, arranged there; and there was the notable success of her sale to the Louvre of her composition “The Frame” (1938), a first buy by that institution of a 20th century Mexican artist.

Kahlo, “The Frame” (1938)

In this unusual self-portrait, Frida Kahlo is experimenting with mixed media. The self-portrait is on a blue background on a sheet of aluminium whilst the border featuring birds and flowers is painted on the back side of a skies that lies on top of the portrait. Some would say this collage had surrealist properties. Even so, she commented bitterly on the surrealist artists she met in Paris. She described Marcel Duchamp as the only surrealist who had his feet on the ground, amongst the “lunatic sons of bitches of the surrealists.”. In Spring she sailed back to America. In 1940, Breton organized the second international surrealist exhibition in Mexico, where her painting “The Two Fridas” (1940) was on display.

Kahlo, “The Two Fridas” (1940)

This painting was completed following Kahlo’s divorce from Riviera, which was short-lived as they subsequently re-married. “The Two Fridas” reveals a super-realist quality described earlier in this essay and some critics see this as reflecting marrying Riviera twice. In the painting are her two different personalities – the traditional with a broken heart sitting next to an independent modern dressed Frida. The main artery which comes direct from the torn heart down to the right hand of the traditional Frida is cut off by the surgical pincers held in the lap of the traditional Frida (see 11).

It would be hard to fit the painting into a surrealist narrative and indeed when completed Kahlo and Breton had lost contact. After the fall of France in June 1940 the Bretons were on the Nazi want-list, but they managed late that year to make an escape over the Pyrenees and reach New York. There were attempts to sustain the surrealist movement by Breton and other emigres in New York, but these were unsuccessful. The cafes of Paris and the networks there could not be re-established. There is no record of Breton continuing to work with Kahlo during these wartime years or beyond. Biographical accounts include reference to a brief Lesbian affair between Lamba and Kahlo but without attaching direct significance for either’s artistic creative work. It remains a question of dispute whether Kahlo was wrong in denying her place in surrealism as awarded by Breton and a range of art consumers and critics.

Notes:

- See Catherine Klingsoehr-Leroy and Uta Grosenick, eds “Surrealism” Taschen 2016

- See Frederico Giannini “Picasso and Rousseau November 1908 a memorable dinner” Fjinestre sull Arte, January 29, 2017ti

- Apollinaire’s poem on the tombstone of Rousseau, appears in Mianjin, vol. 36, No. 3, Spring 1977, p. 365 translator Geoffrey Page

- “Under the Mirabeau Bridge” from “Alcools” by Guillaume Apollinaire, translated by Donald Revell, Wesleyan University Press 1995

- Katherine Mound “Four Pieces of Deeply Philosophical Existentialist Art” in “Culture” August 2, 2016

- “The Bestiary: or Orpheus Procession” by Guillaume Apollinaire in Poet and Poem.com. Translated by A.S. Kline)

- Tere Arco “Far Away from Paris: the surrealist network in Mexico” Shirn Magazine 2020

- Andre Breton “Freedom of Love” in “all Poetry” translated by Edouard Rodti

- “Andre Breton in Mexico: Surrealist visions of an independent revolutionary landscape” Zijng, Nathaniel Hopper, Texas Scholarship Works, 2002