Kazmir Malevich: A Tragic Visionary

by Cathy Locke

I recently returned from Russia and though every time I go there I am flooded with thousands of images of amazing artwork, on this trip the artwork of the Russian Avant Garde painters left me with the strongest impressions. In particular, I learn about the strength and courage of Kazimir Malevich. I knew he was best known for Suprematism, but I really had no idea how he developed this form of art or anything about the artist.

"Supremus No. 58", 1916, oil on canvas

Suprematism

Malevich was very interested in Eastern philosophy and used it as a base from which to work. He felt he was much like God, because he too created things that had never existed before. He said “what I create is not subject or subordinate to any of the laws of nature.” You can take his paintings, like “Supremus No. 58,” and turn it any direction you want and it makes absolutely no difference to your understanding of the work. The painting does not follow any physical law, it has no up or down, it is not ruled by gravity. Malevich felt it was exactly the same as the laws of physics in outer space, or that of the universe.

"Red Square (A Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions)", 1915, oil on canvas

Constructivism

Wassily Kandinsky is considered to be the father of abstraction with his 1910 painting “Improvisation”. I learned on my recent trip that in Russia this painting is called “The War” and in it Kandinsky still holds on to some forms of representation. There are shapes that represent objects such as a dog, solders, lightening and so on. In 1915 Malevich created a painting the world knows as “Red Square” and that he titled “A Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions.” To Malevich this painting was about letting go of all materialism, but to the art world he had created total abstraction and the development of Constructivism. This painting was heavily criticized by his contemporaries at the time he painted it. In response he said, “I am glad I am not like you. I can go further and further into the unknown wilderness of life. It is there where real transformation can take place.” Like Kandinsky, Malevich was exploring themes of spirituality or as he would say Cosmic Space, the idea of the weightlessness of pure form. With the painting “Red Square” Malevich was creating not just a painting, but a symbol. Here we see that the color red is the most active and the color white the most passive. He believed that these two colors represented all the colors of the spectrum. And, by using only these two colors he had represented all color.

In 1912, Malevich painted his first black square. All together he painted four black square paintings. He said he had created a code with this painting that represented all forms of art, because the square was a basic shape used by all types of artists. Again, the use of the color white represented all color in the spectrum, from there Malevich believed the artist could create all other colors. To him the use of the color white in his paintings became a symbol. Below is an Indian diagram that explains Malevich’s theories on the development of his first black square as described in his 1915 manifesto “From Cubism to Suprematism.” You see the black square in the center, this is the concentration of spiritual energy. The small squares around it represent all other civilizations on earth. This is also a kind of motion. In the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg where one of Malevich’s “Black Square” paintings hangs today (the image above), you will notice that the black square is placed in the center between “Black Cross” and “Black Circle”. You will notice in “Black Circle” that the sphere is raised up in the air with the square in “Black Square” firmly in the center. With these two paintings it was his intention to represent a spiritual staircase from the earth to the moon, with “Black Square” representing the earth and “Black Circle” representing the moon. With the painting “Black Cross” Malevich felt the cross was an old symbol of choice. Meaning a cross roads, which in ancient times would be the most dangerous place you could stand. And often it would be the place guards would occupy to protect the ruler’s land.

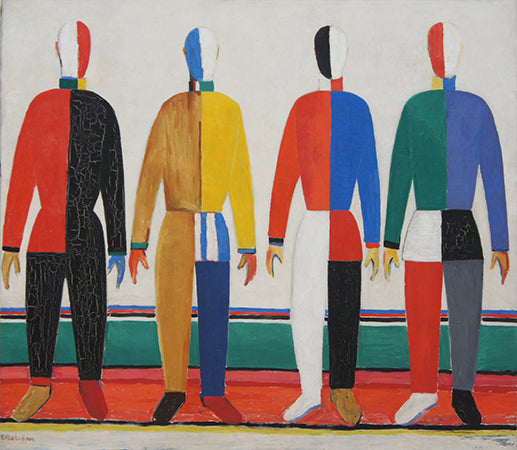

"Girls in a Field," 1928-1929, oil on canvas

In 1928 Malevich started to develop a new direction with his work with his painting “Girls in a Field”. In this painting you see three girls and behind them is a world with bright colors representing a world with no problems. However, this painting is actually a statement on the political oppression that had started in 1924 in Russia. Malevich is actually making a comment on a world that no longer exists. In his painting “Head of a Peasant,”(below on the left) painted in the same time period, you will notice the people are working but you can see their mouths are closed. Malevich was trying to say “don’t speak, don’t tell the truth”. The sky is black to represent that the world that was could not exist anymore. In one of his final paintings of this genre “Two Male Figures” (below on the right) painted in the early 1930s you can see things are getting worse and worse. The figures have no individual identity. Instead of the edges of the forms being hard and crisp which was a characteristic of his work, he now paints rough edges to represent all the irregularities and unstableness going on around him.

The Stalin Years

In 1927 Malevich had his first one man show in both Warsaw and then Berlin. It was his very first recognition by the western art world and his first exposure to any kind of fame for his work. By this time Lenin had died and Trotsky had fallen from power, the period of open idealism in Russia was quickly closing. Stalin was changing the focus of art allowed in Russia by declaring that the only paintings that could be shown had to have “educational value.” At this time there was a large collection of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and Favist paintings in Russia. All of these paintings were taken off of their stretcher bars and rolled, then packed into trains and shipped off to Sibera, because they contained no educational value. Malevich’s work was described by Stalin as “bourgeois” art. His work was confiscated and he was banned from creating and exhibiting. Malevich responded by saying “art can advance and develop for art’s sake alone. Art does not need us, and it never did.” On September 20, 1930 Malevich was arrested and taken to prison. When he was released six months later he was given three choices: 1. He could leave the country; 2. He could close himself in a room and work just by himself; or 3. He could become a realist painter. He did attempt to become a realist painter with a few portrait paintings, including a self-portrait of himself in a Renaissance costume (below). Next he applied his talents tableware, and then clothing where he did have a big influence on costume design.

Malevich developed cancer while he was in prison in 1930. He died of cancer in St. Petersburg on May 15, 1935 at the age of 57. On his deathbed a black square was exhibited above him. In 2002 one of his black square paintings sold for one million dollars to a Russian philanthropist, Vladimir Potanin, who donated it to the State Hermitage Museum collection. It was the largest single private donation in Russia since Lenin’s forced “nationalization” in 1918. In 2008, Malevich’s “Suprematist Composition” from 1916 set a world record for any Russian work of art and sold for just over $60 million. All together he created 85 Suprematism works, of those 22 were lost or destroyed, 47 are in public collections and the rest are held privately. Malevich is responsible for influencing an entire era of artists who were to come.

About the Author

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries and is the editor of Musings-on_Art.org.

Cathy’s artwork: www.cathylocke.com