"The Proud Confidence of a Very Talented Person”

The Biography of Maria Yakunchikova-Weber

by Olga Atroshchenko

Tretykov Gallery Magazine | Issue:#3 2020 (68)

"Cherry Trees," 1897, Watercolour on paper, 33.7 × 28.8 cm., © Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Maria Vasilievna was born on January 19, 1870, into a wealthy merchant family related by blood to the Mamontovs, the Tretyakovs, the Sapozhnikovs and the Alexeyevs. The painter's father, Vasily Ivanovich Yakunchikov (1827-1907), was an industrialist, a Councillor of Commerce, a delegate of the Moscow merchants' community and an elected member of the board of the Moscow Stock Exchange Bank. He owned a cotton mill in the village of Naro-Fominskoye and two brick factories in Troitskoye and Odintsovo. In Moscow, he established shops in the Petrovsky Shopping Arcade Partnership, which he had founded. The painter's mother Zinaida Nikolaevna (1843-1919), nee Mamontova, was the sister-in-law of Pavel Tretyakov and a cousin of the industrialist Savva Mamontov. A charismatic person with an artistic temperament, she played piano very well and was a patron to Alexander Skriabin, whose music she adored.

"A Boat on the Klyazma in Zhukovka," 1888, oil on canvas. 33 × 22 cm. © Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Yakunchikova-Weber was one of the first women in Russia to receive a professional art education, opting for the thorny path of service to art. First, she trained at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, then at the Académie Julian in Paris and, later still, at the printmaker Eugène Delâtre’s workshop, where she mastered the technique of colour etching. In her art, she combined her experience of the Moscow school of painting and the achievements of contemporary European art, becoming one of the pioneers of Symbolism and Art Nouveau in Russia. Yakunchikova-Weber proved herself equally talented in different artforms, such as painting, book design, colour etching and the applied arts. She produced paintings, watercolours, sketches for hand appliqués, toys and clay pottery. She also created painted panels using a technique of her own invention based on pyrography. The artist's creative ambitions resonated with both Russian and European painters. On numerous occasions, she participated in the shows of such groups as “Mir Iskusstva’’ (The World of Art) and “36 khudozhnikov’’ (36 Artists), as well as exhibitions organised by the celebrated Salon du Champ-de-Mars. Teaming up with Konstantin Korovin and Alexander Golovin, she designed the Russian Pavilion's handicrafts section at the 1900 Paris Exposition, where her works received three silver medals. Russian viewers were afforded a chance to see her artwork in its entirety at a posthumous exhibition in Moscow in 1905. This show was organised by her widower Leon Weber.

Contributors to the Anniversary Exhibition

The exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery is the second attempt at a retrospective for Yakunchikova-Weber in Moscow. The exhibition came about thanks to a remarkable event that occurred in recent years: Russia's museums received a large number of Yakunchikova's works, unique photos and archival documents from the collection of Alexander Alexandrovich Lyapin (1927-2011), Vasily Polenov's grandson and Yakunchikova-Weber's grandnephew, who lived in Paris and stayed in close contact with the Weber line of the family. Our museum holds several paintings and graphic works by Yakunchikova-Weber, which the gallery's council bought from the artist's husband in 1910, at the behest of Ilya Ostroukhov. In the 1930s, some of them were sent to regional museums, which have graciously agreed to loan them to the gallery for this anniversary exhibition. Items of particular interest include glass photographic plates from the turn of the century, which were added to the gallery's holdings in 2013 along with other objects from the Lyapin collection and have never previously been exhibited. Several major works have been borrowed from the Russian Museum, some of which once belonged to Princess Maria Tenisheva. In addition, works from private collections significantly enrich our knowledge of the last period of Yakunchikova-Weber's artistic life. The Vasily Polenov Estate Museum is the show's major contributor, lending nearly 130 pieces. Overall, the exhibition features about 200 museum items, including archival documents and pre-revolutionary publications related to Yakunchikova- Weber's life and art.

The Introductory Room (a prelude to creativity)

The exhibition space consists of seven sections and the introductory room, which attempts to recreate the atmosphere of a stately home. At different times in here life, Yakunchikova-Weber spent time at her parents' estates at Vvedenskoye, Morevo and Cheremushki, as well as at the houses where her elder siblings holidayed: Zhukovka, Lyubimovka, Nara, and Borok. The grandeur of the old-fashioned architecture and the beauty of the parks on the estates honed her elegant craftsmanship and marked her manners and lifestyle. According to her contemporaries, aristocratic traits distinguished Yakunchikova-Weber, born to a merchant family, from her numerous relatives. “It was not her words nor her opinions nor her actions but, most likely, something in her manner of acting and feeling that made her stand out from the rest of the crowd, and this distinguished her from her sisters ... I often sensed an aristocratic spirit in this quietly proud consciousness... Or maybe it was simply the proud assuredness of a very talented person,"[1] wrote Alexandra Golshtein.

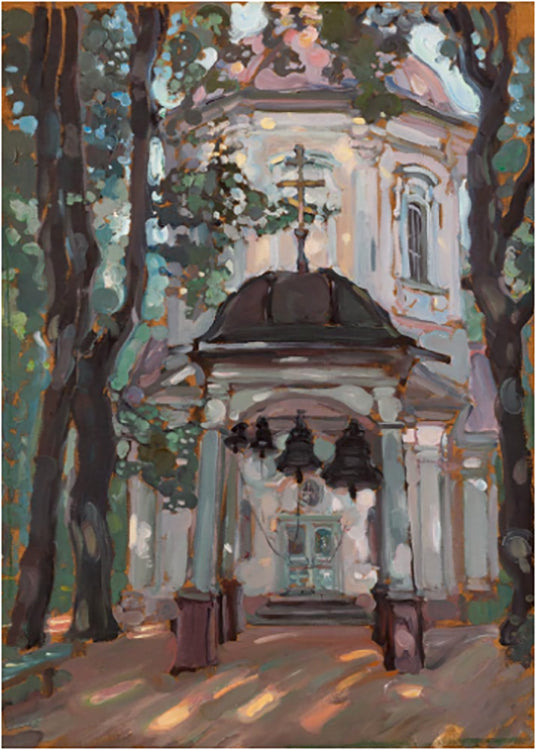

"The Bells. Zvenigorod Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery," 1891, Pastel on yellow paper mounted on cardboard. 42.4 × 33.7 cm. © Tretyakov Gallery

The sale of the Vvedenskoye estate in 1884 pushed Yakunchikova into adulthood and professional maturity. The artist's works on display in this room were inspired by her nostalgia for this bygone era and her suddenly interrupted childhood. The items on view include the pyrogrpahy panels “Dandelions" (1890s), “Aspen and Spruce" (1896) and “Window" (1896), all from the Polenov Museum. The fluffy heads of the dandelions, with their pappi on the verge of dispersing, are, in themselves, symbols of the transience of life, the little aspens and fir trees evoke the Russian scenery that Yakunchikova loved and the cosy window “opening into the old fir tree's greenery"[2] is a painted image of the material world as it comes alive in the clear eyes of a child.

In the other sections (their titles are the titles of the sections in this article), Yakunchikova-Weber's works are grouped by narrative and theme and arranged so as to represent her creative evolution: from her first plein air exercises to her turn towards Symbolism and Art Nouveau. The works of pyrography, book illustrations and etchings are arranged in separate sections, under the title “In Search of New Forms".

Maximilian Voloshin, one of the artist's first biographers, wrote: “She had two periods: the period of global symbols and a lack of strength. Her second stage: the all-discriminating logic of drawing. And in drawing she begins to approach landscape and the symbolism of plants. Human beings remain alien to her."[3]

The artist herself characterised her creative evolution differently. Dividing her works into two groups - the ones created in Russia and the ones created in Europe - she believed she evolved from capturing instances of real life to stylisation and she was equally interested in modernity and the past.

Speaking of style, beginning in the 1890s, Yakunchikova's work was a blend of Impressionism, Art Nouveau, Symbolism and elements of Expressionism with a conspicuous Russian touch.

In 1885 Maria Yakunchikova became a non-matriculated student at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, but it was her friendship with the Polenovs that had an especially strong influence on her creative evolution. In the winter months, the fledgling artist regularly attended the drawing evenings that Vasily Polenov had been organising in his apartment since 1884. The teacher's guests included Konstantin Korovin, Ilya Ostroukhov, Valentin Serov, Isaac Levitan and Sergei Ivanov. It was in their company that Yakunchikova mastered the rudiments of her craft. The sessions normally featured life models (Italian boys, an old man with a scarf around his neck, peasants), but, every now and then, one of the attendees would become the sitter - for instance, Yakunchikova's sister, Natalia Polenova, in an Oriental dress.

"A Street in Florence," 1888, Oil on canvas, mounted on cardboard. 32.2 × 15.4 cm, © Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Three summers in a row, from 1887 to 1889, Polenov rented a big dacha in Zhukovka, near Moscow, to paint en plein air in the company of his students, often joined by Yakunchikova. Polenov observed the young artists' professional growth, cultivating in them good artistic taste and a spirit of fellowship. In the Zhukovka period, Maria developed an artistic bond with Yelena Polenova. Under her older friend's influence, she became interested in intimate lyrical landscapes and the applied arts and, a little later, in book design and the aesthetics of ornament. During that period she was coming into her own as a painter with a distinctive style, as evidenced by her early pieces “Stream on the Klyazma’’ (1888) and “Moscow in Winter: View of Srednyaya Kislovka from the Window" (1889), both from the Polenov Museum. These compositions reflect in full measure the artist's predilection for landscapes with sweeping vistas stretching beyond the horizon. In the realist landscape “Stream on the Klyazma", she used a fragmented composition and a well-chosen colour scheme to create a distinctive world “where all that is ours, local, visible ends, and something new springs into life, something that is just an expectation"[4].

European impressions

In 1889, Maria Yakunchikova settled in Paris and began attending life classes at the Académie Julian. This school was famous for the way it staged its sitters and for its regular classes in anatomy drawing. Even more fascinating for Yakunchikova was contemporary French art. She enthusiastically made the rounds of the museums and exhibitions. In the early 1890s she began to regularly apply Impressionist techniques in her landscapes, attempting to capture the movement of the air, the glittering reflections of sunlight on objects and complex chiaroscuro effects. Her interest as an artist was directed toward the simplest, as she put it, “rather meaningless things"[5]. Yakunchikova enthusiastically produced pictures of pillars with playbills, street lamps, horse-drawn buses and the windows of apartment buildings, but, most importantly, like the Impressionists, she tried to convey the atmosphere when “mist, water, smoke from the chimneys - all has blended into one wonderful grey wetness"[6].

Soon, Yakunchikova-Weber became essentially the first Russian artist to set her sights on the “depressed and wintry" Versailles. As is well known, it was only in the late 1890s that Alexandre Benois began his “Versailles Series", celebrating walks around Louis XlV's famous park. Likewise, nighttime Paris, which captured Yakunchikova-Weber's artistic imagination in the 1890s, had become central to her friend Konstantin Korovin's art by the turn of the century. The artist applied the techniques of the Impressionists in her pastel pieces and she mastered the use of this medium to perfection.

"Church at an Old Estate. Cheryomushki near Moscow," 1897, Oil on canvas. 64.4 × 46 cm, © Tretyakov Gallery

In Russia in spirit

Beginning in 1889, on account of her health problems, Yakunchikova Russia only in the summer. Staying in Morevo, Lyubimovka, Nara, and Borok, she depicted typical Russian scenery, but imbued with a spiritual energy that inspired strong emotions. This is how the writer Anastasia Chebotarevskaya described her impressions of the artist's works: “Every little hideaway in the open air or indoors as portrayed by her offers us the very best, the most sublime experiences, and our eyes are riveted to her unfinished sketches: to the little cluster of corn marigolds against the blue sky, to the chestnut twig with palmate leaves. As the artist herself said, she expressed in her pictures her thoughts and feelings, attaching them to images she derived from real life. And her compositions are not landscapes; they are living poems."[7]

Yakunchikova was especially fond of depicting little pine and fir trees standing in isolation at the edge of a forest: through them, she conveyed a mood of melancholy loneliness. Over the years these trees, like other plants, became, for the artist, more and more closely associated with the country of her birth. Holidaying in a sanatorium in Haute-Savoie, she wrote to Yelena Polenova: “Here I've suddenly found myself in paradisiacal solitude - amidst the moss, bilberries, strawberries, fir trees, and thick grass - the quintessence of Russia's smells, free of any foreign flavours of French nature"[8].

“She built herself a house in Savoie and claimed that everything there reminded her of Russia. Not the hills, of course, but the fir trees, birches, field plants,"[9] confirmed Alexandra Golshtein.

Maximilian Voloshin, carefully studying the artist's legacy, identified another feature of her art. The poet wrote: “Paris and Russia combined in her art to form one seamless whole, mutually complementing each other and filling up her soul in its entirety. Paris, with its ostensible beauty expressed in such clear letters and words, gave her insights into the mystery of speech and gave her the chance to understand Russia. The love for externalities representing Russia could arise only against the background of Paris. Only Paris could teach her to value things so familiar to our eyes that they could no longer see them. There are profound parallels between her views of Russia and those of Paris."[10] Working on an article for the “Vesy" (“Scales") magazine, Voloshin on several occasions visited Leon Weber, the artist's husband, in Chene-Bougeries, hoping to see not only her works, but also her journals - he was denied the opportunity to look at them, with the excuse that they were not yet sorted out. One of the entries in the diaries read: “Why do we need a homeland? Why a dear home, why a dear nook in the garden, if not to grasp things universal and eternal by understanding them?"[11]

Furthermore, Voloshin noticed astutely that that, far from providing the places that were dear to her heart, Yakunchikova-Weber's life abroad raised her sensitivity to the inimitable charm of Russian country estates. “Only in Paris could she gain such an understanding of the profound beauty of the old-fashioned stately homes - that desolate loneliness of the 18th century transplanted to Russia's back country. Only through Versailles could she arrive at compositions such as Dust Covers"[12] wrote the poet. In her works, Yakunchikova-Weber sought not only to represent the majestic buildings and features of the landscapes - gardens, parterres, ponds, main allées - but also to convey her nostalgia for the past. The estate of Vvedenskoye had a special impact on the evolution of her aesthetic ideal.

"A Window in Morevo," 1894, Oil on canvas. 62 × 53 cm. © Ivanovo Regional Art Museum

Reflection of the intimate world

In paintings such as “Reflet Intime" (1894, private collection), “Window" (1892, Polenov Museum), “Dawn" (1892, private collection) and “A Window in Morevo" (1894, Ivanovo Art Museum), Yakunchikova-Weber created an artistic formula that could be used to more strongly highlight feelings and sensations. This formula's elements included the use of metaphorical objects - windows and mirrors - which often reflected a shimmering light from lamps. In the pieces mentioned, her literariness is fading, giving way to visual symbolism[13].

In the artist's mind, the window imagery is infused with personal connotations. She perceived an open window as an invisible boundary between the inner world of her dreams and feelings and the tempestuous, forward-looking life of a city. “There's a lump in my throat, my soul is so overwhelmed by the joy of sadness, the fear of hope, regret over the past, and expectation of the unknown future. Will I be up to the challenge, will I make it? Down there, behind the dark window, Paris is making its noises, life is going on, in need of depiction..."[14] wrote Yakunchikova-Weber in her diary.

"Cemetery in Winter," 1898, Watercolour and gouache on yellow paper. 25 × 25.6 cm. © Russian Museum

In search of new forms

In the late 1890s, Yakunchikova-Weber had mastered the techniques of painting so well that she felt compelled to make this confession: “I don't know why, but it seems to me that for the first time in my life I'm beginning to realise, in most definite terms, what needs to be done in order to advance along the path of life and the path of art"[15]. At that time, the painter was coming up with new artistic idioms and techniques to strengthen the appeal of her compositions. In 1895, she set about producing the painting “A Girl in the Wood" (Polenov Museum). Playing up flexible lines and bright patches of colour, the artist turned forest vegetation into a rich ornamental carpet. The composition remained unfinished, but the idea was used again in the decorative panel with hand appliqué “Girl and Woodsman" (1899, private collection), which won a silver medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition.

It was in this period that Yakunchikova-Weber began to engage with different artforms. Commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev, she produced pieces for print - “Cemetery in Winter" (1898), “Small Town in Winter" (1898) and “Village" (1899) all three at the Russian Museum - as well as numerous headpieces and vignettes. All these works are fine examples of Russian Art Nouveau. Applying the techniques of stylisation, Maria started the production of an ABC book for children, with drop caps taking the form of traditional Russian toys16. This interesting project was not brought to completion - sketches were all that remained - but another piece commissioned by Diaghilev, a cover for the “Mir Iskusstva" magazine, was successfully fulfilled. In 1899, issues 13-24 of the magazine were designed by the artist. The unusually crafted decorative painted panels, which Yakunchikova had been producing since 1895, marked a transitional stage towards book design and the applied arts. Instead of the usual drawing, these panels featured deep elastic lines burnt into the wood. After the pyrography was done, the artist would paint over the composition. Although the production technique was fairly crude, these panels had not only an enormous emotional appeal but also a powerful spiritual energy. In Voloshin's opinion, the pyrography pieces are “the most accomplished and most absolute art that Yakunchikova has ever produced. This style reveals her true face. This style was created and developed by her alone. Her imagery here becomes a sequence of crystalline future-oriented syllogisms."[17]

Konstantin Korovin, "Portrait of Maria Yakunchikova," 1880s, Oil on canvas. 42 × 24 cm. © Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Family photographs and the image of the artist in the eyes of her contemporaries

Writing her reminiscences of Maria Yakunchikova immediately after the artist's death, Alexandra Golshtein viewed her daughter-in-law through the eyes of an out-and-out 1860s woman. “Masha looked nothing like a society girl - she couldn't even master ordinary accommodating manners, and would be the last possible person Frenchmen might find endearing. But much more importantly, her potent talent had no need for imitation or help, but invariably followed its own course always and in every situation."[20]

Perhaps Golshtein wanted to see the image of the person dear to her fit the type of the new woman to which she herself belonged and about which she wrote in her literary work “Recollections of a Former Feminist: Prehistoric Times'": “The new woman: she's in a black dress, her hair cropped, sometimes in blue glasses, but still wearing a hoop skirt"[21]. In fact, the women fitting this description, as least visually, included Yelena Polenova, who always “wore a simple black dress ... with a collar covering her neck", did not indulge in “the slightest affectations of coquetry" and, her femininity notwithstanding, possessed “a nearly male temperament"[22]; another contender was the artist's elder sister, Natalia, with her lifelong allegiance to the ideals of the 1860s. Her daughter Yekaterina remembered her mother as “wispy and gracefully built, in a small jacket of masculine cut"[23]. Maria Yakunchikova-Weber, however, belonged to a different generation. The peak of her creative powers was reached at a time when women in Russia had already won many freedoms and achieved a great deal professionally. Just think of the role played by women in a project to which Russia attached so much importance - the preparation for the International Exhibition in Paris in 1900: the female contributors included Yelena Polenova, Maria Yakunchikova, Natalia Davydova, Elisabeth Boehm, Maria Tenisheva and Natalia Shabelskaya.

In her appearance and demeanour, not to mention her artwork, Maria matched the image of the Silver Age. Judging by the photos featured at the show, the artist was wont to dress elegantly and her splendid chestnut-brown hair, never cut, was always elegantly arranged in fashionable styles. In everyday life, she knew how to create an environment of elevated beauty around her. At the same time, however, one cannot say she belonged to the same class as the outstanding women from the circle of the decadents, such as Zinaida Gippius, Margarita Sabashnikova or Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal, who, in line with one of the concepts of Symbolism, sought to shape their lives into an object of art and outrage. Yakunchikova was able to value the simple pleasures of family life. The birth of her sons and the joy of motherhood filled her life with depths of meaning and revealed new dimensions to her talent. It was then that the artist began to look at national sources, at Russian folklore and folk art, creating fascinating paintings and objects of applied art.

Maximilian Voloshin insightfully noted that the artist was not keen on depicting human beings, the sole exception being the female figure resembling photographs of her that often figured in her pieces. “This is always herself, forever the same, svelte and sad, and you keep the vision of her arms, powerless and thin like the boughs of a birch swaying in the blue sky"[24].

Maria Yakunchikova-Weber died on December 14(27), 1902. By the time of her death, she was an accomplished artist. Alexandre Benois formulated a convincing assessment of her place in the history of Russian art: “Yakunchikova-Weber has an astonishingly endearing creative personality. She is one of those quite rare women who invested in their art all of her female charm, that elusive tender and poetic fragrance, without slipping along the way either into amateurishness or sickly sweetness. ... Maria Yakunchikova is not only a prominent poet but also an outstanding craftsman. This dimension of her artwork is yet to be duly appreciated, but among modern artists - not only in Russia but in the West as well - there are few whose palette is so fresh and noble and whose craftsmanship is so comprehensive and energetic."[25]

Today, Yakunchikova-Weber's personality and artwork still have a magnetic power. Her art is filled with candour, nobleness and aristocratism, and the artist herself inspires our admiration with her courage and the depth of her talent. Seen through today's lens, the fragility and vulnerability of the art of this outstanding exponent of the Silver Age of Russian culture can be regarded as an indispensable prelude to the triumphant rise of the Amazons of the 20th century.

Sources

- Golshtein, A.V. “Maria Vasilievna Yakunchikova-Weber. Memoirs”. Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery, fund 205, item 392, sheet 10 (hereinafter referred to as Golshtein).

- In 1905, there were plans to organise an exhibition of Yakunchikova’s work in St. Petersburg after her posthumous show in Moscow (these plans did not become reality). Organisational matters were the Polenovs’ responsibility. The artist’s works were then kept in the Polenovs’ apartment on Sadovo-Kudrinskaya Street in Moscow, at the centre of revolutionary activity. Yelena Sakharova, the artist’s niece, reminisced: “Her window, opened into the old fir tree’s greenery, the white window ledge, a bunch of cowslips in a little blue pot! In 1905, when we had to move from our apartment near Presnya to our grandfather’s [V.I.Yakunchikov-O.A.] place, my mother [Natalia Polen- ova-O.A.] told me: ‘Take the things that are dear to you’, so I took it.” Kiselyov, M.F. ‘Memoir of Yelena Sakharova “My life’s story”’. “Cultural Heritage. New Findings”. Annual publication. 2001. Moscow. 2002. P. 38.

- Voloshin, M.A. “Collected Works. Volumes 1-17”. Vol. 7. Moscow. 2000, 2003-2015. P. 171.

- Chereda, Yury. ‘Zvenigorodsky uezd (province) (Chekhov, Tchaikovsky, Yakunchikova)’. “Mir iskusstva” (The World of Art). 1904 (5). P. 103.

- In one of the letters, she wrote: “I must confess that what attracts me there are kitchen gardens, narrow passages between fences with clothes drying on them, sunflowers, footpaths, wasteland, and the monotonous life of a rural town. This may be odd, this may be wrong, but my soul has quite fallen asleep here, and I’m making do with fairly meaningless things”. From Maria Yakunchikova’s letters. Late 1880s - 1890s. Department of Manuscripts, Tretykov Gallery, fund 205, item 32, sheet 1.

- From Yakunchikova’s letter to Yelena Polenova. Paris. November 27 (December 9), 1891. Sakharova, Ye.V. “Vasily Polenov and Yelena Polenova: A Chronicle of the Artists’ Family”. Moscow. 1964. P. 470. Similar feelings are expressed in her letter to Natalia Polenova: “Today there is that wonderful, dark, wet weather that makes you want to move mountains”. Polenova, N.V. “Maria Yakunchik- ova. 1870-1902”. Moscow. 1905. Pp. 18, 15. (Hereinafter referred to as Polenova.)

- Anastasia Chebotarevskaya (1877-1921) was the wife of the poet Fyodor Sologub and an activist of the women’s movement. She saw Yakunchikova-Weber’s works at her posthumous exhibition in Moscow in 1905. Impressed by her art, Chebotarevskaya wrote an article called “Friend artist. (Postmortem exhibition of Maria Yakunchikova’s works)” and published it in the “Russkaya Mysl” (Russian Thought) magazine in 1905. Institute of Russian Literature, fund 189, No. 19, sheet 3.

- From Yakunchikova’s letter to Yelena Polenova. Hotel des Montées. June 18, 1898. Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery, fund 54, item 9707, sheet 1.

- Golshtein, A.V. Sheet 10.

- Drafts of Voloshin’s article for the “Vesy” (Weighing Scale) magazine. Institute of Russian Literature, fund 562 (Voloshin), inv. 1, No. 189, sheet 1.

- Kiselyov, M.F. “Maria Yakunchikova”. Moscow. 2005. P. 30.

- Voloshin, M.A. ‘Art of Maria Yakunchikova’. Vesy. 1905 (1). P. 35. (Hereinafter referred to as Voloshin, M.A.)

- Voloshin makes interesting observations. He writes: “Compare Velazquez - a reflection in a mirror. A reflection on transparent glass is much subtler. But more realistic.” And he goes on: “A reflection in a window. A Velazquezian mirror. A window as a symbol. Flowers in a window: the demarcating line between the ghostly and the internal. Flowers as a symbol of the eternal joy of external life. This joy comes to them when it feels the first touch of death.” (Voloshin, M.A. ‘The History of My Soul’. “Collected Works. Volumes 1-17”. Vol. 7. Moscow. 2000, 2003-2015. Pp. 168, 170.)

- Kiselyov, M.F.; Yakovlev, D.Ye. “The Diary of Maria Yakunchikova: 1890-1892”. “Cultural Heritage. New Findings”. Annual publication. 1996. Moscow. 1998. P. 485. (Hereinafter referred to as The Diary.)

- From Yakunchikova’s letter to Yelena Polenova. Chamonix, June 18, 1898. Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery, fund 54, item 9707, sheet 2.

- Yakunchikova-Weber began contemplating the ABC book after the birth of her son Stepan in 1898. Unfinished, the book exists as a mixture of odd sketches and drafts. Several years later, in 1904, Alexandre Benois published his “Alphabet in Pictures” and 1911 saw the release of Elisabeth Boehm’s alphabet.

- Voloshin, M.A. P. 37.

- Uzanne Octav. “Modern Colour Engraving. With Notes on Some Work by Marie Jacounchikoff” // “The Studio: an illustrated magazine of fine and applied art”. London: Offices of the Studio, 1896. Vol. VI. P. 148-152. Bibl.Beraldi H., “Evgene Delatre, peintre-graveur et imprimeur. Revue de l’art ancien et moderne”, juin 1905$ Heintzelman A.W., Evgene Delatre , The Boston Public Library Quarterly, juillet 1952$ I.F.F., apres 1800, vol. VI, 1953

- Golshtein, A.V. Sheet 10.

- Golshtein, A.V. Sheet 8. Yakunchikova’s diary contains this entry: “Along the way, in a carriage, the conversation turned to T.S. [aunt Sasha, A.V. Golshtein-O.A.], who doesn’t know me at all; later, up at the hotel, Maka [Leon Weber-O.A.] and I talked about it and I told him how distressing it was that I was made out as serious and green Masha while I was completely red, light-headed. How I wish I didn’t have to contain myself and were sure that I’m loved with my faults, and not just with my fictitious virtues that are a figment of imagination.” (The Diary. P. 489.)

- Golshtein, A.V. ‘Recollections of a Former Feminist: Prehistoric Times’. “Preobrazhenie” (Transfiguration). 1995(3). P. 71.

- ‘Just think of all the occasions when she proved herself useful...’ Yegishe Tadevosyan’s memories of Yelena Polenova. “Yelena Polenova. 160th Anniversary”. [Album] Moscow. 2011. P. 356.

- Kiselyov, M.F. “Memoir of Yelena Sakharova: ‘My Life’s Story’”. “Cultural Heritage. New Findings”. Annual publication. 2001. Moscow. 2002. P. 24.

- Voloshin, M.A. P. 38.

- Benois, Alexandre. “History of Russian Painting of the 19th Century”. Issue 1. St.Petersburg. 1901. Pp. 245-246.